Everything to Everyone

It's an impossible mission, so why do we still try?

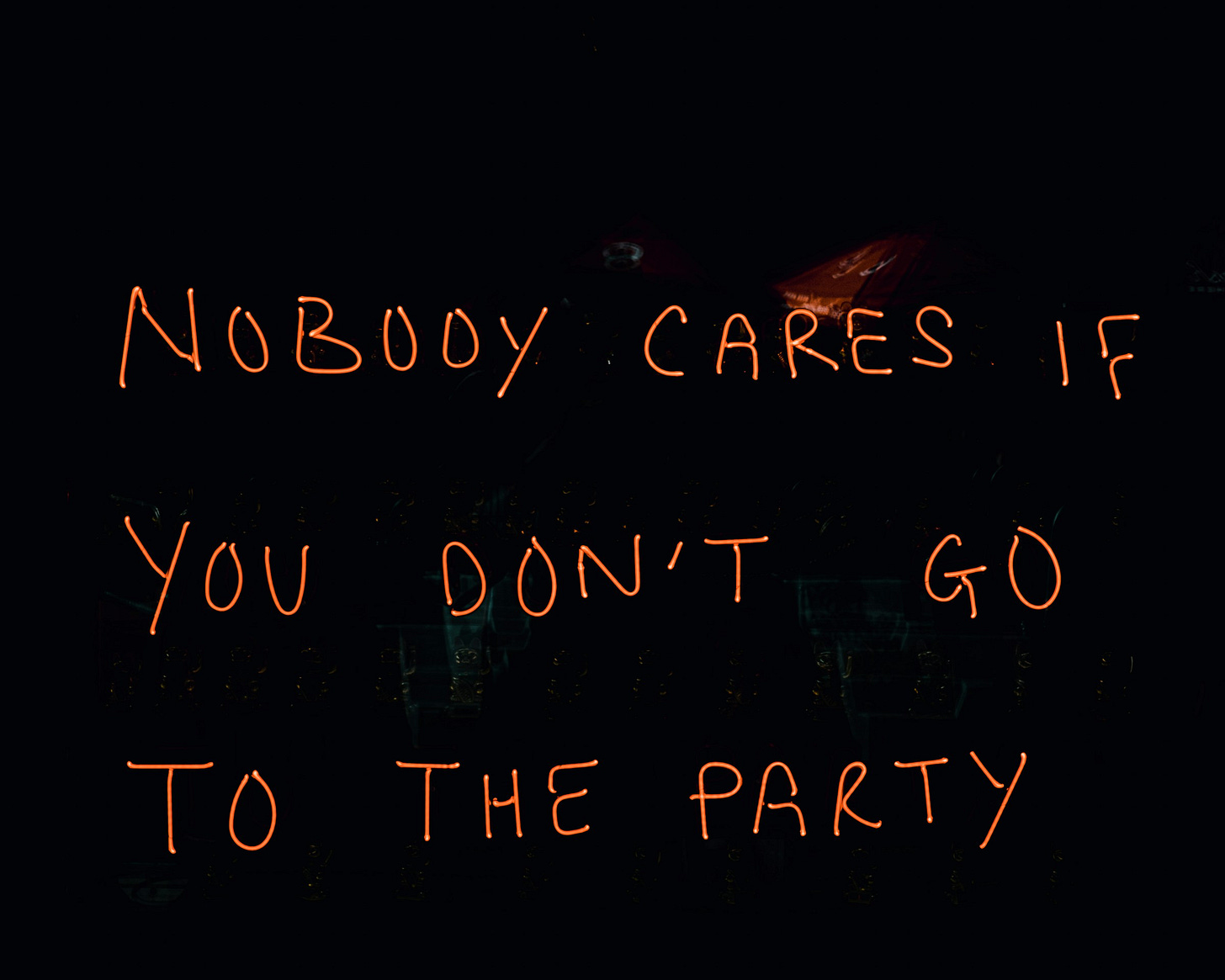

“Don’t try to be everything to everyone.”

This is one of those life principles that we’re just supposed to “know”—but then we ignore it and try to make everyone happy.

The advice is hard to follow because it conflicts with a basic human instinct: the desire to be liked. Even if you don’t think of yourself as a people pleaser, chances are you still appreciate being appreciated.

I understand the paradox firsthand. In fact, I’m embarrassed to say that I’ve had to learn it over and over! Even though my first “online brand” was The Art of Non-Conformity, I still spent a lot of time in my early days trying to win over people who didn’t get it.

When I received complaints from readers, instead of politely wishing them well and moving on, I’d spend hours writing long messages to them, assuming I could persuade them to see my logic through clever argument or just sheer force of will. It rarely worked, of course, and I could have spent that time doing any number of other things.

If You’re Good at Getting People to Like You, It’s Even Harder

Sometimes, however, trying really hard to get someone to like us actually works. The bad thing about it working sometimes is when it reinforces our belief that we can change other people’s minds.

It’s called operant conditioning, developed by psychologist B.F. Skinner. It refers to the idea that behavior can be trained through rewards (reinforcement) or punishments, depending on the desired outcome. You’ve probably heard of the studies, how rats learn to follow a maze or push a lever to get a reward. They do it because they’ve learned to associate the behavior with a reward.

This same intermittent reinforcement happens in relationships—sometimes our people-pleasing works, which keeps us trying even when it doesn't.

In Skinner’s experiments, the main variable that increased the rats’ persistence was intermittent reinforcement. If a behavior works every time and then it stops working, a smart rat will quickly give up. But if it works every once in a while, they’ll keep trying, over and over!

This short video (4 minutes) presents operant conditioning with other examples:

What Can We Do?

We can’t just decide to not be everything to everyone. We have to actually live it out! It takes effort and practice.

Well, I suppose first it begins with acceptance—we have to understand that we’re not going to be liked by everyone, and that this is a normal part of life.

But then, the what-do-we-do-with-it part kicks in. Here’s my suggestion:

Instead of trying to change your instincts, change your questions. Next time you catch yourself trying to win over someone who isn't interested, ask:

What am I trying to prove, and to whom?

What would I create if I knew half the people would hate it?

Who already appreciates me as I am, and how can I invest more in those relationships?

What would happen if I let this person be wrong about me?

Am I trying to convince them, or am I trying to convince myself?

These questions don't make the urge to be liked go away, but they might help you pause long enough to choose a different response.

My intense need to make sure people like me comes from trauma.

As a kid, I had Stockholm Syndrome.

I had no choice — I absolutely had to put all my energy into making the psychopaths who raised me feel connected to me to survive.

While not everyone’s caretakers are as sick and damaged as mine were, the reality is that many of us knew on a psychological level that we needed to help our caretakers care for us.

We needed to make ourselves as likable as possible so they would perform the caretaking we needed to survive.

We “helped them” “help us.”

So it makes sense that now, as adults, we feel survival terror if people don’t like us.

Because if our caretakers had not liked us, our survival actually was in danger!

I won’t get into just how dangerous my childhood was, but as an example, these people who were charged with my care sometimes starved me because it failed to register that I needed food after surgery, or money for food while I was in college.

These patterns are very deeply ingrained and tough to root out.

As usual, Chris, I love this friendly opener to these issues.

I love how you normalize the experience of the deep and sometimes intense urge to get people to like us.

And I also want to invite an Internal Family Systems perspective — if these deep rooted urges to people please don’t respond to initial efforts, it may be simply because they are wound up in traumas that need deeper healing.

So if you can’t get on top of them, I invite you not to criticize yourself.

Simply consider it may take deeper therapy to really get to the root of the issues.

I couldn’t get this solved without deeper work.

As I unwind the traumas that fuel these patterns in me, my people pleasing is diminishing. It’s such a relief.

This inner work is ridiculously hard, but ridiculously worth it!

Thank you, Chris. For the first time, I have been ghosted. I rediscovered a former classmate after many years. I wanted to be friends. She had no interest in the past, of which I was a remote part of. It was HARD not to take that personally.